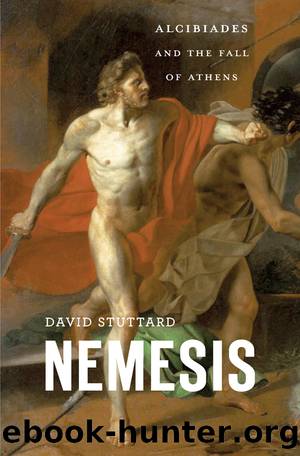

Nemesis : Alcibiades and the Fall of Athens (9780674919662) by Stuttard David

Author:Stuttard, David

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Harvard Univ Pr

Sardis: satrapal seat of Chithrapharna and site of the Paradise of Alcibiades. (Photograph by the author.)

Undoubtedly, one of the main instigators of Spartaâs new hostility was Agis. His motives were not just personal (his wifeâs adultery) but intensely political, too. For much of his early reign, Agis had been sidelined, condemned for his attempts at diplomatic settlements, patronized for his poor military skills. Even now, he was at Decelea only because Alcibiades had persuaded Spartaâs ephors to send him there. Yes, he was achieving much. But last winter, when the Spartans were debating which strategy to backâthe one Agis favoured (to accept Farnavazâs support and secure the Hellespont) or Alcibiadesâ preferred option (to win over Ionia)âthey had supported Alcibiades. And since then, what talk there was in Sparta had been dominated by accounts of Alcibiadesâ brilliance, as if he were singlehandedly responsible for every victory. Which rankled. And not just with Agis. With many of the other strutting Spartan and Ionian egos, too. So, they had gone to the ephors with accusations, undermining Alcibiades, questioning his motives, and, when the seeds of doubt had sprouted, demanding he be killed. Yet Alcibiades still had loyal friends in Sparta, among them Queen Timaea, and they smuggled out the message, which snaked its way across the sea and inland to the satrapâs palace. Alcibiades was forewarned.22

By now, though, he was already sloughing off his ties with Sparta and immersing himself wholeheartedly in Persian life. It is possible he took a crash course in the Persiansâ language. Certainly, he embraced their lifestyle, tying his hair up in a bun, curling his well-oiled beard (a symbol of machismo in the Persian court), dousing himself in the perfumes for which Sardis was so famous, and dressing not just in sumptuous robes and beautifully fringed tunics of linen, wool, and mohair (deep-dyed in vibrant reds and vivid yellows, and adorned with ornaments in glittering gold foil), but in those other garments so associated by Athenians with decadent, eastern effeminacy: trousers.23

Unquestionably, too, sitting beside Chithrapharna, in a special place of honour, as his âtablemate,â bejewelled and with a characteristic Persian signet ring hanging from a golden chain around his neck or wrist, he enjoyed the legendary hospitality of the satrapâs court: banquets held in dining rooms hung with close-woven tapestries and strewn with the softest carpets, while, in the torchlight, concubines plucked harps and sang soft, soothing songs in eastern cadences as, languidly, still others danced; the sweet red wines of Sardis; mezés of fragrant stews and flatbreads, followed by the sweetest of desserts; and, on Chithrafarnaâs birthday, the greatest feast of all, perhaps a mouth-watering indulgence of roast oxen, horses, asses, camels, cooked whole in huge ovens, and carved before the guests. This was a day of lavish present-giving. But not to Chithrafarna. From him. In Persia, the powerful bound their subjects to them through their largesse, and a painstakingly judged hierarchy of gift-exchange proclaimed the recipientâs place in the tight social order.24

If feasting was part of the performative display of power, so, too, to Alcibiadesâ delight, were horses and horse racing.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Blood and Oil by Bradley Hope(1566)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1430)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1394)

Daniel Holmes: A Memoir From Malta's Prison: From a cage, on a rock, in a puddle... by Daniel Holmes(1336)

Twelve Caesars by Mary Beard(1324)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1300)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1174)

What Really Happened: The Death of Hitler by Robert J. Hutchinson(1167)

London in the Twentieth Century by Jerry White(1149)

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(1135)

Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger(1131)

Twilight of the Gods by Ian W. Toll(1123)

A Woman by Sibilla Aleramo(1097)

Cleopatra by Alberto Angela(1096)

Lenin: A Biography by Robert Service(1080)

John (Penguin Monarchs) by Nicholas Vincent(1072)

The Devil You Know by Charles M. Blow(1029)

Reading for Life by Philip Davis(1027)

The Life of William Faulkner by Carl Rollyson(994)